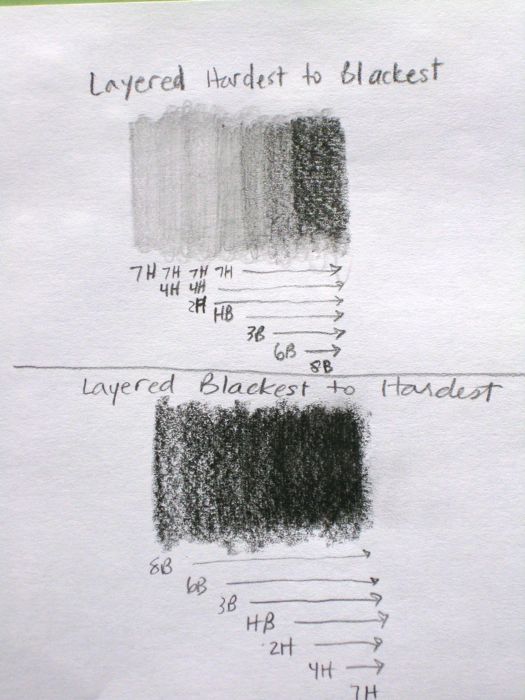

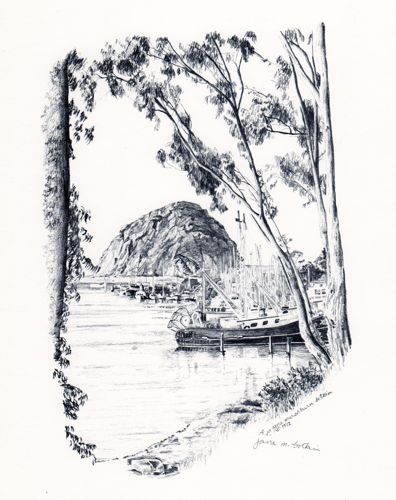

Pencils are made from a blend of graphite and clay. If they have more clay, they are harder and lighter. If they have more graphite, they are blacker and softer.

H is for Hard, B is for Black. I don’t get why those two are considered opposites in Pencil World. (Hey Pencil Manufacturers, tune in here!)

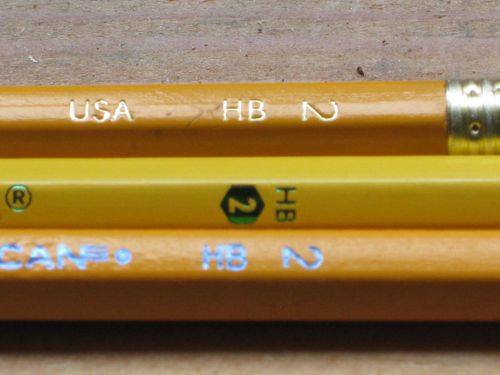

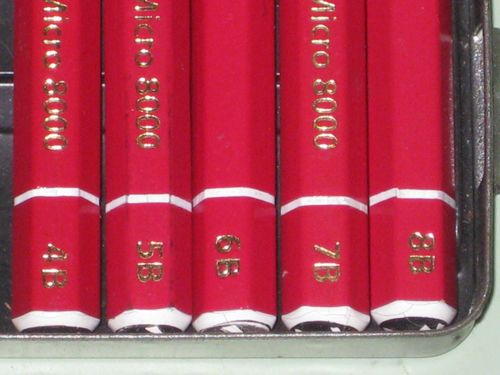

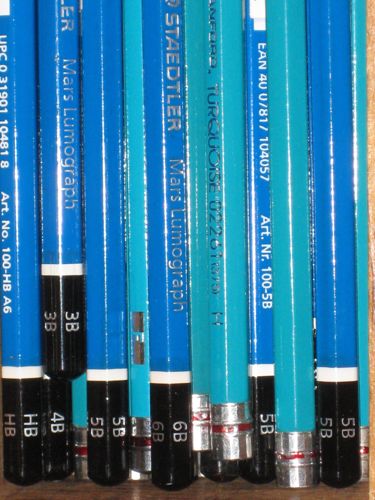

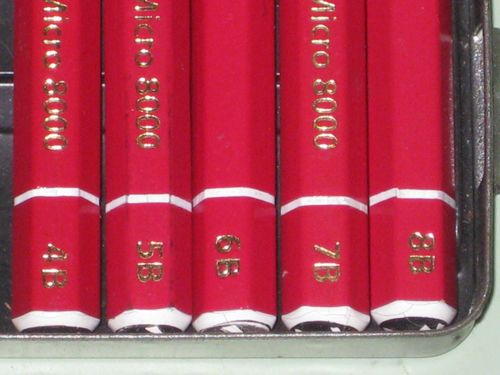

Usually the H and the B are accompanied by a number, usually 2 – 6, but occasionally as high as 9 depending on the brands. If there is no number with the letter, a 1 (one) is implied. HB is right in the center. F is an unnecessary interloper that shouldn’t be included in a set because it takes up space that could be better used for a more useful pencil. I’d like a set without an F and with an extra 6B, please. (Pencil manufacturers, are you listening??)

The higher the number, the more the particular quality of that pencil. A 6H is very hard, very pale, and very easily scratches the surface of the drawing paper. A 6B is very black, very soft, and will crack, crumble or collapse internally if you so much as frown in its direction. This is why I’d like a second 6B included in a set of pencils. (Hey Pencil Manufacturers, I’m talking to you!!)